GovTech expert shows you how to prevent cyber eavesdropping

Electromagnetic radiation emitted from electronic devices could compromise privacy and security. GovTech’s Mr Tan Peng Chong shares how organisations can better protect their digital assets from external eavesdropping and influence.

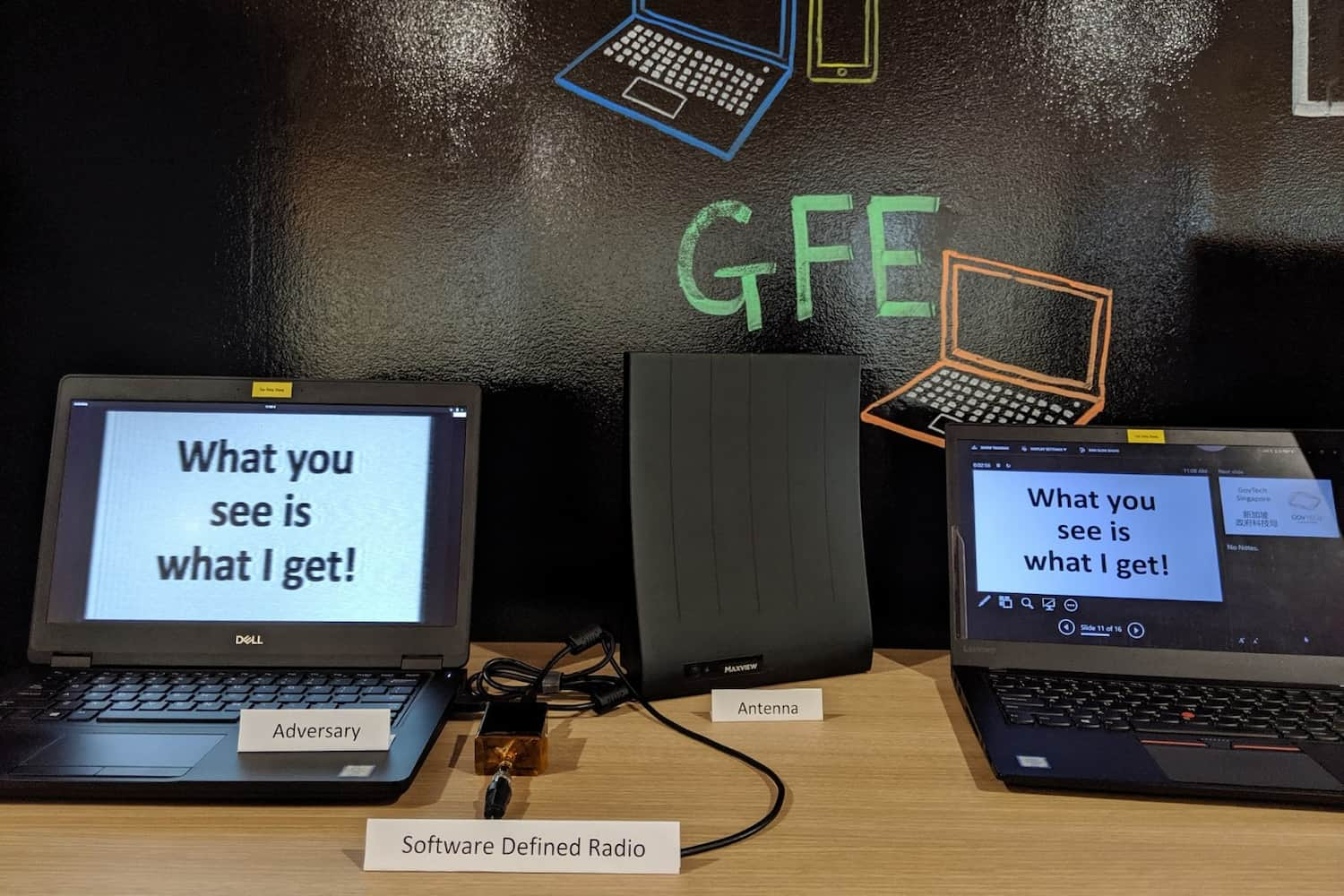

An antenna, a radio device and a laptop; innocuous as these objects may seem, in the right (or wrong) hands, they can be assembled into a formidable tool for eavesdropping. Mr Tan Peng Chong, principal cybersecurity specialist at the Government Agency of Technology (GovTech) Singapore, knows this all too well.

Tasked with securing government assets against cyber threats, he has experimented with the numerous methods that hackers may use to obtain private information illicitly.

During a brown bag seminar at GovTech’s Mapletree Business City headquarters, Peng Chong demonstrated precisely how a malicious actor could remotely view what a victim is doing on a computer screen using—you guessed it—an antenna, a radio device and a laptop.

Configuring those contraptions, Peng Chong was able to mirror the screen of another computer in the room on his laptop. Any action performed on the would-be victim’s computer was now visible to him in real-time.

Tuning in to the right channel

So, how did Peng Chong do it? Put simply, electronic devices emit electromagnetic (EM) radiation when they process information. This radiation propagates like radio waves that are used for television or radio broadcasting.

The principle is simple: any electrical current flowing through a conductive wire generates an EM field. “Whenever devices switch bits—from zero to one, one to zero—they subtly emit EM waves,” Peng Chong explained. “[These waves] can be picked up and used to reconstruct the information that the devices were processing].”

So, in a sense, most devices broadcast their activities to the world, albeit with very faint signals. The technology to tap into EM emissions has, in fact, been available since World War I, deployed by military forces to listen in on the enemy’s communications over field telephones.

Although commercial electronics are seldom designed to protect against [EM emission-based] surveillance, Peng Chong notes that many consumer electronic devices today run on much lower voltages, which means that their EM emissions are generally much less obvious. A spy or hacker would, therefore, need more sensitive antennas and related equipment or be within closer range of their victims to siphon off private information.

Plugging the emission leak

Peng Chong indicated three possible countermeasures for those concerned about becoming victims of such attacks: shielding, filtering and masking. While all three approaches may sound similar, they differ in their implementation. Like most cyber defence strategies, there is no one-size-fits-all solution, and each person or organisation will have to decide for themselves which strategy—or combination of strategies—is most suitable for their applications, after factoring in the risks, cost and usability.

Evolving emission security threats

Besides remote surveillance at a system level, Peng Chong said that an emerging cybersecurity concern is the exploitation of EM radiation at a microscopic level onto small security components such as the Trusted Platform Module. Moving from passive EM eavesdropping, a new dimension is the exploitation through injecting EM faults into the security components. If successful, the fault could reveal further vulnerabilities to a hacker or even allow the hacker to recover cryptographic keys.