Using AI to differentiate different types of mosquito larvae

Did you know there are more than 180 species of mosquitoes in Singapore? That’s more than the United States, which has 176 mosquito species.

The most common types in Singapore are the Aedes (which spread dengue and chikungunya), Culex (which spread filariasis), and Anopheles (which spread malaria). The National Environment Agency (NEA) actively monitors mosquito populations, and correctly identifying different species is an integral part of enabling targeted measures to eradicate mosquitoes.

To aid NEA in its fight against mosquitoes, GovTech teamed up with the agency to explore the feasibility of using Artificial Intelligence (AI) based video analytics to identify mosquito larva species. And the first step was to understand how the job is being done by humans now.

How is mosquito species identification done today?

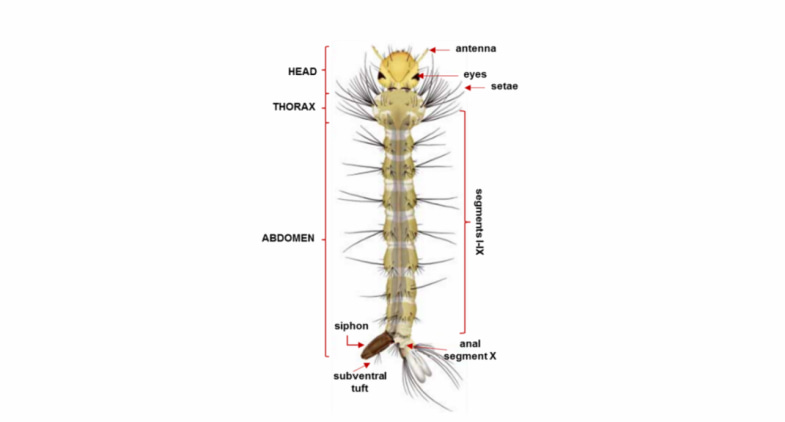

Currently, trained analysts examine taxonomical characteristics of mosquito larvae through a microscope. A mosquito larva observed through a microscope would look like this:

Anatomy of mosquito larvae. Source: OECD Publication.

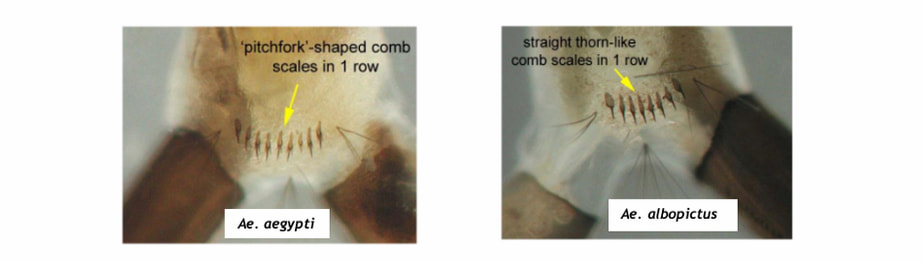

A mosquito larva typically has an ovoid head, thorax, and abdomen of nine segments. Analysts look for subtle differences to identify different species. For example, the Ae. aegypti (left) has pitchfork scales, while the Ae. albopictus (right) has thorn-like scales.

Source: Florida Medical Entomology Laboratory

As you can see, analysing mosquito larvae remains a challenging task due to the high resemblance of various species, especially those within the same groups. The distinctions among different species are difficult to identify even for human experts with the naked eye, as subtle distinctions can only be observed through microscopic scrutiny. Methods of larvae image analysis mostly rely on manual work, which can be labour-intensive and prone to human error.

How did GovTech approach the problem?

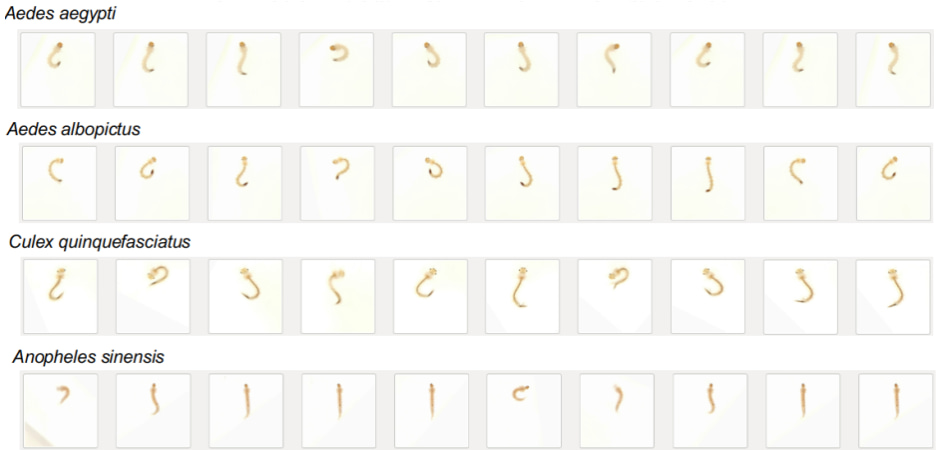

When we saw several studies indicating that different mosquito species may exhibit different movement patterns, the team explored the use of video analytics to classify larvae. We focused on the four most common species in Singapore:

-

Aedes aegypti,

-

Aedes albopictus,

-

Culex quinquefasciatus, and

-

Anopheles sinensis

Getting the dataset of videos

NEA used a consumer-grade mobile phone to capture about 6,800 high-quality videos of between 5 and 50 seconds. The videos were filmed in a controlled environment so that the lighting, angle and focus were consistent, providing a “cleaner” dataset.

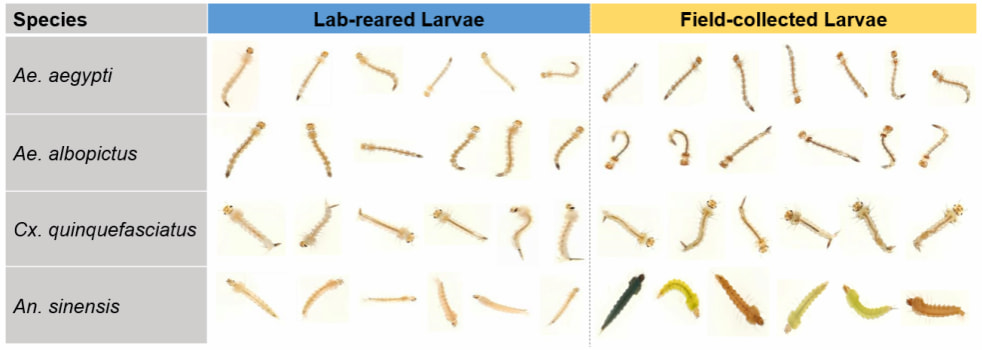

About 92 per cent of the videos came from lab-reared samples. As they were grown in a controlled environment, the larvae had fewer variations within a species in terms of size, colour, body texture, and movement patterns. The field-collected samples, which were harder to obtain, had more diverse features, as seen below.

Comparison of lab-reared and field-collected larvae. (Source: National Environment Agency)

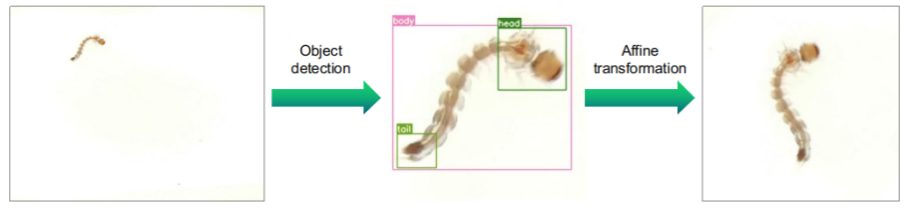

Next, we took still images from the videos at fixed intervals and then used an automated process to detect the area of interest where the larva is, crop the images to a consistent size, and rotate the images so that the head was on top.

Pre-processing steps. (Source: GovTech and National Environment Agency)

These steps produced a sequence of images that can be analysed for differences in the motion of different species.

Examples of pre-processed inputs. (Source: National Environment Agency)

These images are then split into two sets: the training and test sets. The training set is fed into the AI model – a neural network called CNN-LTSM that is good at handling sequences of video frames. The model learns from the training set to recognise different movement patterns in the video frames. After it has been trained, the model is then shown the previously unseen test set and is tasked to predict which species the video frames come from.

How did the AI model perform?

When we first started the project, only lab-reared sample videos were available. Using this limited dataset, we were able to achieve more than 99 per cent in weighted F1 score, which judges how accurate the model is! The model could not only correctly classify species from different groups (Aedes vs. Culex vs. Anopheles), but it also managed to differentiate seemingly lookalike species (Ae. aegypti vs. Ae. albopictus) from the same group. This was not surprising as the lab samples were consistent in appearance within the same group.

However, when the lab-sample-trained model was tested on the field-collected samples, the F1 score dropped to about 89 per cent. Clearly, the different appearances of field-collected larvae gave the model difficulties. For example, the appearance of lab (left) and field (right) Ae. aegypti looked very different.

Colour and pattern differences in lab-reared (left) and field-collected (right) samples. (Source: National Environment Agency)

We had known of this problem and tried to adjust for it by adding random colour differences to our lab-collected images. However, this solution was clearly not enough to mitigate the problem.

Subsequently, we introduced more field samples to train the model and after a few iterations, we were able to build up our F1 score to almost 100 per cent!

What lies ahead

The result of the project has demonstrated the viability of using AI to classify the four most common species of mosquito larvae in Singapore.

However, there are a few caveats to note. The end-to-end process, including image processing and model training, is computationally expensive. Also, while the model can recognise the four species effectively, we don’t know how well it can handle new species that it has not seen. It will likely have to be retrained for every new mosquito larva we introduce.

Nonetheless, this project has set the stage for developing complex AI models to handle challenging object classification problems and we are excited about enhancing it further to apply to other cases!